Laura Weinstein

A Sufi. Bijapur, Deccan, circa 1650. Nim Qalam (brush drawing and watercolour on paper), 9.5 x 6 cm.

The art of India’s Deccani sultanates has been described as “the stuff of dreams.” Mythical creatures, paradisiacal gardens and wandering mystics populate paintings and drawings created for the Deccani sultans and the nobles who served them, and these extraordinary elements infuse the art of the region with vitality, whimsy, and spiritual significance.

Sufism – the mystical branch of Islam – is the source of much of this supernatural imagery. Sufi saints, who had become well-established in the Deccan by the early fourteenth century, played important roles in the cultural and political world of the Deccan. They endorsed the authority of the sultans, transmitted knowledge of Islamic beliefs to the broader populace, and helped to expand vernacular literature through the composition of Sufic poetry and songs. These contributions were supplemented by others more occult such as advising kings on how to harness magic and foretelling the future.

Images of Sufis in paintings from Bijapur emphasize the mystical and magical elements of their character. One well known painting in the Bodleian Library depicts a Sufi saint receiving ash-smeared visitors, perhaps coming in search of knowledge or training. An outsized white bird perches in the tree behind the elevated saint, inexplicable and marvelous. A group of illustrations in the Nujum al-Ulum – a manuscript about mysticism and kingship created in Bijapur in 1570-71 –depicts a bearded, Sufi-like figure conjuring spirits and leading other occult rituals.

The image of a Sufi offering a flower in this catalog (no. X) is related closely to another way of representing the Sufi in Deccani painting: as a lone figure on a spiritual quest, having abandoned worldly possessions to seek union with the divine. Unlike the images of Sufis as figures of authority just described, this Sufi is not a man of obvious power, though his austerities may earn him great respect. On the contrary, he is weak and gaunt, stands in a hunched position, and in some representations, stumbles along on a horse that appears even worse off than he. His profound suffering marks him as a man in pursuit of a lofty spiritual goal.

More supplicant than purveyor of magical powers, the Sufi in catalog number X is emaciated, his ribs visible and his legs stick-thin. Suffering is evident in the deep lines around his eyes. He wears a thin cloth around his shoulders and an animal skin around his waist. A small bag hangs off of one hip, while a crescent-shaped horn swings from the other. These are the accoutrements of a wandering dervish, seen also in images such as a drawing by the Mughal artist Basawan of a figure identified as a Kanphata Yogi. While the yogi raises his hands in a gesture of entreaty, the figure in catalog number X proffers a flower to an invisible recipient, perhaps a Sufi of greater stature as in yet another drawing by Basawan. His fur-lined cap, out of which spring sprigs of a flowering plant, hints at the figure’s eccentric nature and suggests that he inhabits a realm beyond social norms.

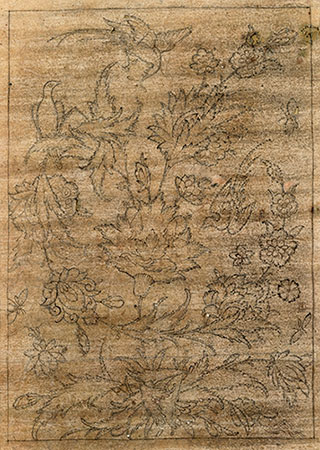

Like the flowers that our Sufi wears in his unusual cap, the blossoms depicted in catalog no 3. are drawn from the natural world but they point to something quite beyond it. Related to a large number of drawings and paintings of flowers produced in the Deccan in the seventeenth century, this image depicts a plant that is closer to the paradisiacal illumination of Persian and Indian manuscript pages than to natural history illustration. It is from the latter, however, that this kind of imagery probably derives. In particular, it comes from European herbals in which whole pages are devoted to the depiction of a single botanical specimen against a plain background. In North India, Mughal artists adapted imagery from such herbals in paintings produced for Jahangir, who was keenly interested in the natural world. Deccani artists also produced paintings and drawings of this kind, many of which contain less botanical detail and three dimensional modeling than Mughal examples. Even with these differences, however, it can be difficult to say conclusively which are from the Deccan and which are Mughal.

Pheasants amongst Peonies and Lotuses. Golconda, Deccan, circa 1620-30.

Nim Qalam (brush drawing and watercolour on paper), 9.7 x 6.7 cm.

In this drawing, which is likely to have been produced in Golconda, a vine sprouts out of a central peony and then sweeps counter-clockwise around it, nearly forming a complete circle. A shorter vine springs from the center to the upper right corner of the page, bearing another large blossom. Pheasants swoop across the page and perch on the vine, while small insects and butterflies flock towards the blooming flowers and jagged-edged leaves. The composition is related to that of another Deccani image in which bursting flowers and birds in flight swirl about a central, multi-colored palmette.

In catalog no. 3, as well as in many other Deccani paintings and drawings from the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, flowers assume fantastic shapes, colors and proportions. Not merely ornamental, they can represent the realization of spiritual perfection towards which mystics strive. Flowering plants are the most common of all decorative motifs, and yet in Deccani art they are not at all banal; on the contrary, they stand in for the many splendors of paradise.

Flowers find an even more fantastic setting in catalog number no. 4, an expertly executed decorative drawing. Two boldly-drawn vines spiral outwards from a central point at which two dragons clash, sprouting flowers and leaves as well as creatures along the way. Drawings such as these – in which animal heads grow out of winding vines – have long been identified as patterns for metalwork, book-bindings and other types of objects, but they are also accomplished works of draftsmanship in themselves.

The insertion of creatures into decorative patterns and vine scrolls has a long history in Persian art, and dates back at least to the twelfth century. It is often referred to as the “waq waq” design after the legend of Alexander and the talking tree. Artists in India used this manner of enlivening their work extensively, and in Golconda in particular we find many examples. A particularly impressive one is the frontispiece of a Persian medical encyclopedia in the Chester Beatty Library in which the illumination is filled to bursting with animals and mythical creatures. They not only inhabit but constitute the structure of the illumination, as where a row of angels stretch out their wings to create a boundary between a blue and a gold band of decoration. An inhabited decorative drawing attributed to Golconda in the collection of Jagdish and Kamila Mittal is very close to catalog no. 4, and may have been produced by the same workshop. The Mittal drawing is markedly similar to a copper salver in the same collection, and it is not difficult to imagine that our drawing was also created with metalwork in mind. Despite these close connections to Deccani material, the attribution of drawings such as this one is not totally secure since Mughal and Persian artists also worked in this mode throughout the seventeenth century.

In these three drawings we see Deccani artists exploring fantastic imagery in a number of different ways. In an image of a wandering Sufi, mystical struggle and yearning are represented through the physical weakness of the figure and his eccentric accoutrements. A burst of flowers in the second drawing introduces abstraction and exuberance to the art of botanical documentation, creating a tableau of foliage suggestive of the bounty of paradise. Mythical creatures inhabit and merge with vegetal elements in the third drawing, turning a simple decorative drawing into a supernatural menagerie. Each of these examples of Deccani draftsmanship displays not only the skills of the region’s artists but also the delight they took in representing visually the transcendent worlds of imagination, mysticism and paradise.

Laura Weinstein

Boston, MA

Detail: Inhabited Arabesque: Golconda, Deccan, circa 1600-10. Nim Qalam (brush drawing on paper), 9.5 x 18 cm.

i. George Michell and Mark Zebrowski, Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 1.

ii. Ms. Douce Or. b.2(1), fol. 1a. See Mark Zebrowski, Deccani Painting (London and Berkeley, CA: Sotheby Publications, University of California Press, 1983), color plate VII.

iii. Chester Beatty Library, Ind Ms 2. See Linda York Leach, Mughal and Other Indian Paintings from the Chester Beatty Library (London: Scorpion Cavendish, 1995), vol. 2, 819-89.

iv. For a discussion of these images see Zebrowski, Deccani Painting,135-8 and Deborah S. Hutton, Art of the Court of Bijapur, Contemporary Indian Studies (Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 2006), 146-155.

v. Harvard Art Museums, 2009.202.255. See Stuart Cary Welch and Kimberly Masteller, From Mind, Heart, and Hand: Persian, Turkish, and Indian Drawings from the Stuart Cary Welch Collection (New Haven, London and Cambridge, MA: Yale University Press and Harvard University Art Museums, 2004), no. 21. This example is in a very similar style to our drawing: thin, delicate lines are used to great effect in the depiction of fur, hair and the volume of limbs.

vi. A Mughal image depicting one Sufi offering a flower to another, by Basawan, is in the British Library (Johnson Album 22, no. 13). See Toby Falk and Mildred Archer, Indian Miniatures in the India Office Library (London and Delhi: Sotheby Parke Bernet and Oxford University Press, 1981), no. 2. Basawan, like the artist of our drawing, uses the nim-qalam technique to depict scenes of Sufi life.

vii. Michell and Zebrowski, Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates, 184. For examples of other flower studies attributed to Golconda, see Linda York Leach, Paintings from India (London and New York: Nour Foundation in association with Azimuth Editions and Oxford University Press, 1998), no. 66 and 67.

viii. Ind Ms 30. Leach, Mughal and Other Indian Paintings, vol. 2, 889-891.

ix. Stuart Cary Welch, Indian drawings and painted sketches, 16th through 19th centuries (New York: Asia Society, 1975). No. 28.

x. Inv. No. 76/1442. Mark Zebrowski, Gold, Silver and Bronze from Mughal India (London: Alexandria Press in association with Laurence King, 1997), no. 580.

If you would like to stay up to date with exhibitions and everything else here at Prahlad Bubbar, enter your email below to join our mailing list